Imagine stepping onto the sun-drenched deck of a contemporary lakeside cottage, where the air is crisp and the design feels effortlessly chic. Instead of the typical weathered grey or honey-toned wood, the structure is wrapped in a breathtaking, velvety black timber. Against the vibrant green of the surrounding forest and the sparkling blue of the water, the cottage looks like a crisp ink drawing brought to life. This is the modern face of shou sugi ban, an ancient Japanese craft that has evolved from a rustic survival tactic into the ultimate statement of luxury.

This Japanese method of preserving wood by charring it with fire has surged in popularity, transforming from a pragmatic rural necessity into a high-end design staple. Whether you see it on the sleek façade of a mountain retreat or the textured accent wall of a Manhattan loft, shou sugi ban is the ultimate “baptism of fire” for timber.

The Origins of Craft

The technique, more accurately known in Japan as yakisugi, dates back to at least the 18th century. Historically, Japanese villagers sought a way to protect their wooden homes, primarily made of Sugi (Japanese cedar) from the brutal coastal elements. In a brilliant twist of logic, they realized that by burning the surface of the wood, they could make it resistant to the very things that destroyed it: fire, rot, and insects.

There is a poetic irony in this “fireproof by fire” logic; an old Japanese sentiment suggests that “the charred remains of a house will not burn again.” While not literally fireproof, the carbonized layer has a much higher ignition point than raw wood, creating a natural fire retardant. Originally, this was a “poor man’s” preservation method, often utilizing driftwood harvested from the shores, which had already been seasoned by salt and sun.

The Technique: The Dance of the Flame

While modern practitioners often use propane torches for precision, the traditional method is still practiced by specialists like Nakamoto Forestry, is a spectacular sight.

- The Flue Method: Three long planks of Sugi are tied together to form a triangular chimney.

- Ignition: A fire is started at the base, and the “chimney effect” draws the flames upward, charring the interior faces of the boards in seconds.

- Quenching: The boards are untied and immediately doused with water to stop the combustion.

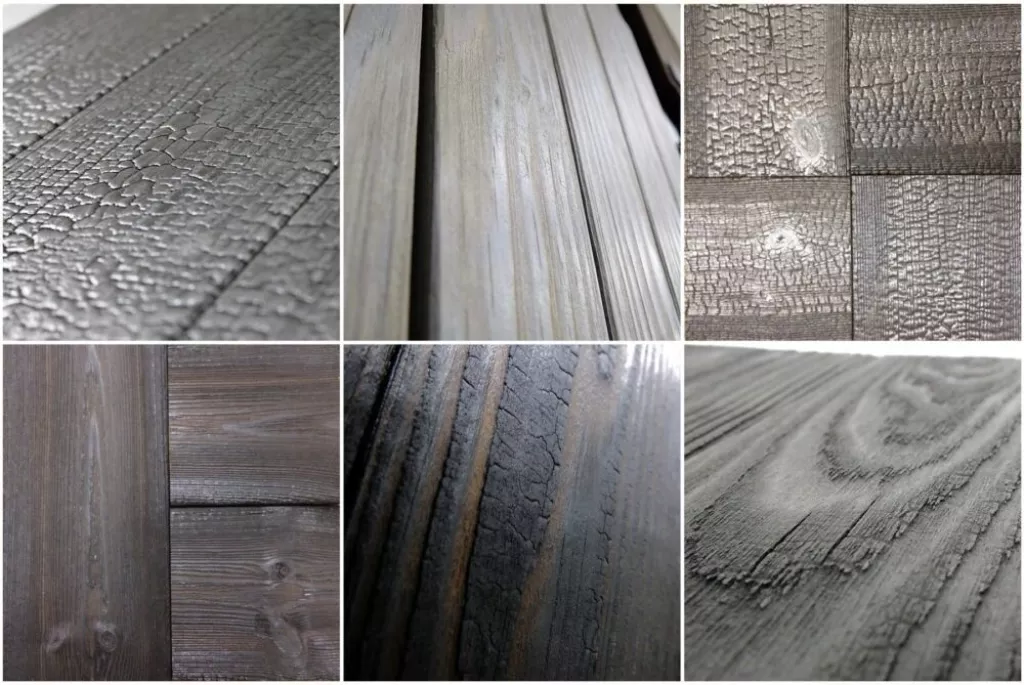

- Finishing: Depending on the desired look, the soot is either left thick and “alligator-skinned” (suyaki), brushed back to reveal the grain (gendai), or heavily polished with oil (pika-pika).

Why It’s Trending: The Wabi-Sabi Appeal

Beyond its durability, shou sugi ban has captured the imagination of the design world because it is a non-toxic alternative to chemical pressure-treatments. It appeals deeply to the Wabi-sabi philosophy: finding beauty in imperfection and the natural cycle of growth and decay. The deep, obsidian-black hue achieved through fire is impossible to replicate with paint; it possesses a “living” quality, changing its shimmer as the sun moves across it.

Interestingly, the very name “shou sugi ban” is a Western linguistic quirk. The Japanese characters are correctly read as Yaki Sugi Ita (burnt cedar board). While “shou sugi ban” has stuck in the West, calling it Yakisugi will earn you immediate respect from traditional woodworkers who know that, properly maintained, this siding can last 80 to 100 years.

The Designers and the Visionaries

The revival of this technique in global modern architecture is often credited to the renowned Japanese architect Terunobu Fujimori. His whimsical, charred structures especially the Too-High Teahouse, reintroduced the world to the tactile power of burnt wood.

Today, interior designers and architects have pushed the boundary of how the material is used. It is no longer just for siding; it is a tool for interior atmospheric depth. Designers like Kaspar Hamacher have taken the flame to the furniture world, “sculpting” wooden stools and benches using fire as a primary carving tool. This creates a piece that feels less like a product and more like a relic.

Iconic Projects

To see the best examples of this technique, one must look at how it interacts with light and other materials:

- The W Hotel, Boston: This is a premier example of shou sugi ban (provided by Delta Millworks) used in a luxury commercial setting. The charred wood is paired with mirrors, marble, and brass. The contrast between the rough, burnt timber and the polished stone creates a “moody luxury” that defines modern hospitality.

- The Oak Hill House (London): Designed by Claridge Architects, this project uses thin, diagonal charred slats to create a rhythmic, textured exterior. It demonstrates how the ancient technique can look incredibly sharp and “high-tech” when applied with mathematical precision.

The Oak Hill House | Claridge Architects Limited - The Falcon (New York): This is a restaurant-bar with a dark, charred exterior allowing the building to “disappear” into the shadows of the surrounding forest, proving that fire can actually help a man-made structure harmonize with nature.

The Falcon | Falcon - The Cinna & Ligne Roset Showroom (Limoges): Here, charred wood is used as a backdrop for high-end furniture, showing how the matte black texture of the wood absorbs light, making the colors of the furniture pop with theatrical intensity.

The French Living

Shou sugi ban is more than just a “black wood” trend; it is a philosophy of resilience. It teaches us that through the most destructive elements like fire can create something that is not only more beautiful but also significantly stronger. As we move toward a future of sustainable, “slow” design, this ancient Japanese gift of fire and cedar is likely to remain the hottest trend in the industry for years to come.

References

- https://kebony.com/blog/shou-sugi-ban-6-reasons-why-shou-sugi-ban-is-the-hottest-trend-in-architecture/

- https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/shou-sugi-ban-black-waterproof-wood-furniture

- https://www.thespruce.com/what-is-shou-sugi-ban-yakisugi-5119876

- https://nakamotoforestry.co.uk/2022/12/06/yakisugi-vs-shou-sugi-ban/

- https://woodworkersinstitute.com/charring-and-blackening-wood/

- https://www.ubm-development.com/magazin/en/shou-sugi-ban-baptism-of-fire/

- https://aertsen.in/what-is-shou-sugi-ban-and-why-is-it-trending/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/19/t-magazine/shou-sugi-ban.html

- https://www.barrons.com/articles/the-trending-look-that-has-home-designers-playing-with-fire-3b14ef21