Given that the majority of people on earth live in urban areas and spend over 90% of their time indoors, architecture has a significant impact on human wellness. Nonetheless, the architecture of both built and unbuilt areas is primarily created with the visual sense being prioritised over the other senses.

Yet in recent years, more and more designers and architects have begun to include the other senses—sound, touch, smell, and, on rare instances, even taste—into their work. The multimodal nature of the human mind has evolved from the field of cognitive neuroscience study, yet little is known about it as of yet.

“Experience comes first, forms much later” -B.V. Doshi (Ashutosh Shah, 2014)

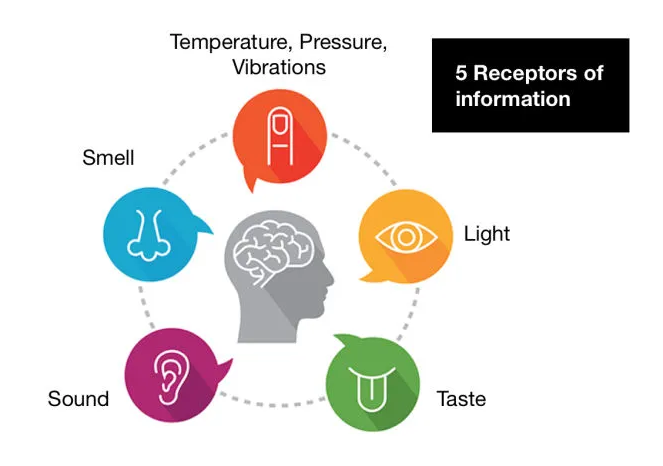

When we experience a space, we experience it through our senses and as we all know, we have five of those. (Fig 1) That is five different resources for designers to explore and tap into.

Let’s see how we, as designers can design for each of the senses:

- Sight

There are many uses for visual perception, but it is the primary sense and the most significant one for a designer. Light, colour, and form are only a few examples.

Consider, for instance, how the trapezoidal balconies on the renowned The Future apartment building at 200 East 32nd Street in Manhattan deceive the eye (Fig 2)

When viewed from one side, they appear to slope downward, while when viewed from the other, they appear to slope upward.

Another example of visual perception can be seen in the use of colours.

Take the work of Mexican architect Luis Barragan, otherwise known as the architect of colour. Barragan’s style can be recognised from the distinctive colour palettes he uses.

The Torres de Satélite ( Fig 3) are a group of sculptures located in Mexico designed by Barragan keeping in mind the visual design in an urban sculpture of great dimensions.

2. TOUCH

Materials come in all forms – some are polished, others are raw, some are warm, others are cold, some are even made to interact with their surroundings.

One of the most enigmatic architects of the 20th century, Carlo Scarpa is known for his instinctive approach to materials.

The work of Scarpa is a prime example of multi-sensory design. Bringing together time-honoured crafts and modern manufacturing processes, the Italian architect has embraced contrasts and made them his trademark. His renovation of the Castelvecchio museum in Verona, (Fig 4) completed in 1964, is an ode to materials and tactility.

3. SOUND

A change in acoustics can have an impact on the entire space. Deep pile carpets create an aural sense of warmth while marble floors and glass walls convey an aural sense of coldness. It is all about reverberation time.

This sense is the most important when designing public spaces such as airports, schools, libraries, hotels, etc.

So how can our hearing be stimulated in architecture? Ambient music is an obvious example. Water is an underrated one. Acoustics is key. A classic example of using water is The Singapore Jewel Waterfall at the Changi Airport. (Fig 5)

In the words of acoustic consultant Julian Treasure, “It’s time to start designing for our ears”. In a 2012 TED talk, Treasure talked about “invisible architecture”, stating that poor sound affects our health, our education and our productivity in the workplace.

4. SMELL

“We all have our favourite smells in a building, as well as ones that are considered noxious. A cedar closet in the bedroom is an easy example of a good smell.”

Scents trigger memories, we associate spatial qualities to them: “it smells like home”, “it smells like a hospital”.

If cleverly used, these associations could be utilized in architecture to increase certain emotions, to create a complete brand experience or even, like the Chinese used to with beautifully engineered incense clocks, to tell the time.

For example, landscape design with different fragrant flowers, the smell of the earth, rooms with artificial aromas, or even an open kitchen, that allows the smell of fresh food to permeate the environment.

5. TASTE

When, in his book Architecture and the brain, Eberhard (2007, p. 47) talks about what the sense of taste has to do with architecture, he suggests that: “You may not literally taste the materials in a building, but the design of a restaurant can have an impact on your ‘conditioned response’ to the taste of the food.”

“The suggestions that the sense of taste would have a role in the appreciation of architecture may sound preposterous. However, polished and coloured stone as well as colours in general, and finely crafted wood details, for instance, often evoke an awareness of mouth and taste. Carlo Scarpa’s architectural details frequently evoke sensation of taste.” – Pallasma

FINAL TAKE ON MULTISENSORY DESIGNS AS AN ARCHITECT

The experience of architecture could involve multiple senses. To create buildings that are more intense and exciting, architects must use the factors. There is little doubt that these events have a big impact on people.

We learn from our experiences; it’s a part of life. The purpose of architecture is to meet the demands of human activity, which establishes a connection between the senses of people and the constructed environment. A space can come to life when all five senses are present. An active environment and atmosphere don’t seem to be only possible by designing architectural form and function that is primarily for the visual sense, but also engages all of the senses in a space so the shape and performance could also be fully expressed so occupants can have deeper and more meaningful moments.

Designers should be aware that a space might be exciting in many ways than one, even though it is not required to design for all senses at once. Think of your place as a well-balanced instrument that can communicate with its users through a variety of senses. What can you do to please users and who is your target audience?

Design for the senses.